The Atlas of Canada - Physiographic Regions

Abstract

Canada’s landscape is very diversified and comprises several distinctive areas, called physiographic regions, each of which has its own topography and geology. This map shows the location of these physiographic regions, including their subregions and divisions.

These are the physiographic regions of Canada:

- Canadian Shield

- Hudson Bay Lowland

- Arctic Lands

- Interior Plains

- Cordillera

- Great Lakes - St. Lawrence Lowlands

- Appalachian Uplands

The Canadian Shield

The landscape of the Shield has been levelled by many long periods of erosion and presents an even, monotonous skyline interrupted by rounded or flat-topped summits and ranges of hills. The surface of the Shield is mainly the result of glaciation and a great proportion of it is covered by water in the form of lakes, ponds and swamps. The most outstanding characteristic of the Shield is the similarity of the terrain, whether you are in Labrador, northern Quebec and Ontario, or the Northwest Territories.

The Canadian Shield is divided into four subregions:

- Kazan Region

- Davis Region

- James Region

- Laurentian Region

Kazan Region

The Kazan Region is located in the northern part of Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and also covers parts of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. It consists of vast areas of massive rocks that form flat, broad, sloping uplands, plateaus and lowlands. The Kazan Region is divided into several subregions: the Coronation Hills, the Bathurst Hills and the East Arm Hills; the Boothia Plateau and the Wager Plateau; the Kazan Upland and the Bear-Slave Upland; the Athabasca Plain, the Thelon Plain; and the Back Lowland.

The following photographs are examples of the type of terrain found in the Kazan Region.

Figure 1: Northwestern Manitoba - This photograph, taken in northwestern Manitoba, shows an aerial view of gravel ridges that mark the location of crevasses in the ice sheet that once covered the Canadian Shield. Each ridge is about 3 metres high and 10 metres wide.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2001-079. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 2: Boreal Forest, Northwestern Manitoba. This photograph, taken in northwestern Manitoba, shows the typical landscape of glaciated Shield terrain in the boreal forest.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2001-081. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 3: Lac de Gras, Northwest Territories. This photograph, taken north of Lac de Gras in the Northwest Territories, shows a typical glacial landscape in the Canadian Shield.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2001-184. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services.

Davis Region

The Davis Region extends from Ellesmere Island south and southeastward to northern Labrador. The general aspect of its landscape is that of a broad, old erosion surface almost without surficial deposits. Viewed from an elevated location, the landscape presents an even horizon interrupted by rounded or flat-topped ranges of hills. Along the eastern coast, the relief is generally high. The region is divided into a northern insular part and a southern mainland part. The subdivisions are the Davis Highlands and the Labrador Highlands; the George Plateau and the Melville Plateau; the Frobisher Uplands, the Hall Uplands and the Baffin Uplands; the Baffin Coastal Lowlands and the Whale Lowlands.

The following photographs show examples of the terrain from the Davis Region.

Figure 4: Torngat Mountains, Labrador. This photograph, taken in the Torngat Mountains of Labrador, shows the arêtes and horns around Mount Caubvick.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-405. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 5: Baffin Island, Nunavut. This photograph, taken on eastern Baffin Island in Nunavut, shows a glacier flowing off the Byam Martin Mountains ice cap near Navy Board Inlet, which divides Baffin and Bylot islands.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-238. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

James Region

The James Region exhibits the characteristic features of the Shield that are apparent in major uplands and plateaus. This region spreads from the centre of Manitoba to Labrador, lying south of the Hudson Region. The James Region encompasses several subregions consisting of hills (Port Arthur, Penokean, Mistassini, Labrador and Povungnituk), plateaus (Saglouc, Larch, Caniapiscau and Lake), uplands (Abitibi and Severn), plains (Nipigon and Cobalt) and lowlands (Eastmain).

The following photographs show examples of landscape from the James Region.

Figure 6: Témiscamingue area, Quebec. This photograph shows an esker located west of Témiscaming village, in Témiscamingue area of Quebec.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2004-093. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 7: Rapide-Sept area, Quebec. This photograph shows large dunes in the Rapide-Sept area of Quebec.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2004-097. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Laurentian Region

The Laurentian Region comprises uplands and highlands that rise abruptly above the St. Lawrence Lowlands along their northwestern border. It borders the St. Lawrence Lowlands from Georgian Bay to the Atlantic Ocean and includes the Laurentian Highlands, Mealy Mountains, Mécatina Plateau, Hamilton Plateau, Hamilton Upland, Melville Plain and Lake St-Jean Lowlands.

The following photographs show examples of landscape found in the Laurentian Region.

Figure 8: Walker Lake near Port-Cartier, Quebec. This photograph of Walker Lake, near Port-Cartier in Quebec, emphasizes the typical terrain found in the Canadian Shield north of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In the background are rolling, glacially eroded hills of granite and gneiss, which are covered with a thin mantle of till. In the foreground, Boreal spruce forest surrounds a lake excavated by the ice sheet during the last glaciation.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2001-272. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 9: North Shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Quebec. This is a photograph of St-Nicholas fjord, a long, narrow inlet on the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, which can be seen in the background. The inlet is a glacial valley that was created when the ice sheet flowed southeastward into the area now occupied by the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2001-278. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

The Hudson Bay Lowland

The Hudson Bay Lowland form the main central depression on the surface of the Canadian Shield. The Hudson Bay Lowland is a low, swampy plain with subdued glacial features and a belt of raised beaches that border the Hudson Bay.

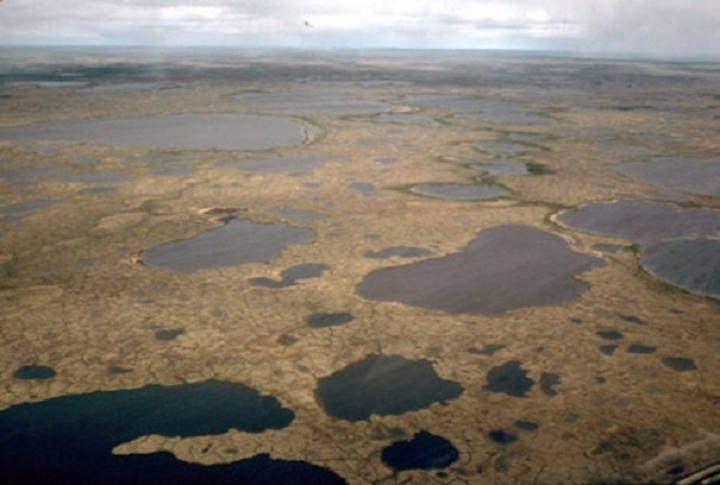

The following photographs show examples of landscape found in the Hudson Bay Lowland.

Figure 10: Hudson Bay Lowland, Manitoba. This photograph, taken in the Hudson Bay Lowland of northern Manitoba, shows patterned ground north of the treeline in an area covered with peatland permafrost. The 'crackled' pattern is produced by ice wedges in the sphagnum peat. Shallow ponds, called thermokarst depressions, have formed at sites where ground ice has melted out.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2001-121. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 11: Attawapiskat River, Ontario. This photograph was taken at the mouth of the Attawapiskat River on the James Bay coast in Ontario. The Attawapiskat River reaches James Bay after crossing the Hudson Bay Lowland, an immense low-relief wetland.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-385. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

The Arctic Lands

The Arctic Lands are divided into three subregions:

- Innuitian Region

- Arctic Coastal Plain

- Arctic Lowlands

Innuitian Region

The Innuitian Region is characterized by two zones of mountains that are separated by extensive and discontinuous terrain of more subdued topography formed by plateaus, uplands and lowlands.

The mountain ranges include the Grantland, the Axel Heiberg, and the Victoria and Albert mountains. On central Axel Heiberg Island and northwestern Ellesmere Island, the mountains are nearly buried by ice sheets through which the peaks project as a row of nunataks. Between these two large mountainous zones lies the Eureka Upland. To the south are the Perry Plateau and the Sverdrup Lowlands, a region of low relief, rolling, and scarped lowland.

The following photographs show examples of landscape found in the Innuitian Region.

Figure 12: Svendsen Peninsula of Ellesmere Island, Nunavut. This photograph, taken on Starfish Bay, on the Svendsen Peninsula of Ellesmere Island, shows Arctic fireweed (Epilobium latifolium) of the Evening Primrose family.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-270. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 13: Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut. This is an aerial photograph taken at the head of Whitsunday Bay on Axel Heiberg Island.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-272. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Arctic Coastal Plain

The Arctic Coastal Plain includes the coastal terrain along the shores of the Arctic Ocean from Meighen Island to Alaska. It is divided into three divisions, each of which has distinctive physiographic characteristics:

- The Island Coastal Plain extends from Meighen Island to Banks Island, sometimes characterized by hilly terrain that carries an ice cap and sometimes by a low, flat, uniform landscape or by low hills;

- The Mackenzie Delta includes not only the delta of the present river but remnants of earlier deltas and features built by the deposition of a mix of sediments coming from the river and from the sea. A multitude of lakes and channels cover the Mackenzie Delta plain and, in the older parts, pingos form the most outstanding features of the landscape;

- The Yukon Coastal Plain, which lies at a higher altitude than the Mackenzie Delta, appears to be largely an erosion surface cut into bedrock and mantled by a thin veneer of recent sediments.

The following photographs show examples of the landscape of the Arctic Coastal Plain.

Figure 14: Prince Patrick Island, Northwest Territories. This photograph of Prince Patrick Island in the Northwest Territories shows beach lines (in the foreground) developed as the land rebounded from the sea in the last few thousand years following disappearance of the ice sheet from the region. The beach sediments became cracked by permafrost.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-331. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 15: Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories. This photograph, taken near Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories, shows two pingos, which are ice-cored mounds covered by soil. Pingos occur in permafrost terrain and are common in this area. These features along the coast are about 40 metres in height and protrude above a flat landscape lying between low uplands and the sea.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-704. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Arctic Lowlands

The Arctic Lowlands include the Lancaster Plateau, Foxe Plain, Boothia Plain, Victoria Lowland and Shaler Mountains.

The surface of the Lancaster Plateau slopes gently southward from about 770 metres on southern Ellesmere Island, across central Devon Island, to an average elevation of 300 to 600 metres on Somerset Island and the Brodeur Peninsula of northwestern Baffin Island. The landscape is uniformed. Farther south, the surface descends still lower until it forms the surface of the Boothia Plain on both sides of the Gulf of Boothia.

Surrounding Foxe Basin, the landscape of the Foxe Plain is low and smooth. It forms a very shallow basin-like area on the old surface, partly covered by very shallow sea. Farther west, the Shaler Mountains rise through the Victoria Lowlands.

The following photographs show examples of the landscape from the Arctic Lowlands.

Figure 16: Peninsula on Baffin Island, Nunavut. This photograph of Brodeur Peninsula, located on Baffin Island in Nunavut, shows a broad flat plateau that was eroded to near sea level before the glacial period. The deep river gorges were cut into it as it was lifted to its present level following the retreat of the ice sheet.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-204. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 17: Hall Beach on the Melville Peninsula, Nunavut. This photograph of Hall Beach, located on the Melville Peninsula in Nunavut, shows an expanse of low, even topography. Tundra meadows with shallow ponds, together with low, cobbly beach ridges (in the foreground), are typical of many extensive parts of this region.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-504. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 18: Igloolik Island, Nunavut. This photograph, taken in late summer on Igloolik Island in Nunavut, shows low mounds on a raised beach (on which the geologists are walking) where sod-and-whalebone houses of the Thule aboriginal culture are located.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-562. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

The Interior Plains

The Interior Plains occupy the region between the Canadian Shield on the east and the mountains of the Cordillera on the west. They join with the Great Lakes - St. Lawrence Lowlands of eastern Canada through the United States and are separated from the Arctic Lowlands by the Amundsen Gulf. The southern part is characterized by semi-arid prairie, the central part is tree covered and the northern part is covered by the tundra. The region is divided into several subdivisions, those in the north being smaller and more varied than those in the south.

In the north, the Horton and Anderson Plains form the Arctic slope. The Peel Plain, which lies southwest of the Mackenzie River, forms a broad, shallow hollow in which some areas have innumerable small lakes and others have none.

West of the Peel Plain, the Peel Plateau rises in steps between the Peel Plain and the Mackenzie Mountains. On the east, the Colville Hills embrace several ridges that stand above the general level of the surrounding plains. Located around Great Bear Lake, the Great Bear Plain has a rolling surface. In contrast, the Great Slave Plain has generally little relief.

Located in the centre of the Interior Plains, the Alberta Plateau consists of a ring of plateaus separated by wide valleys. The two main valleys (Fort Nelson and Peace River lowlands) occupy more than 50 per cent of the area. These two rivers and their main tributaries are more or less entrenched into the valleys.

South of the Athabasca River, the Alberta Plain stretches southeastward to the Canada–United States boundary. Although a continuation of the Alberta Plateau, it has a more even surface, with a few widely separated groups of low hills, such as Cypress Hills in the south. The Cypress Hills reach an elevation of more than 1400 metres.

The eastern edge of the Alberta Plain forms a step down to Saskatchewan Plain, which is lower and smoother than the Alberta Plain. On the east, the Saskatchewan Plain is bordered by the Manitoba escarpment, overlooking the Manitoba Plain. Streams flowing eastward have deep cut valleys, which divide the Manitoba Plain into a line of separate hills. The Manitoba Plain is largely covered by lakes and includes most of Lake Winnipeg.

The following photographs show examples of landscape from the Interior Plains.

Figure 19:Athabasca River, Alberta. This photograph of the Athabasca River, taken near Whitecourt in central Alberta, shows the subdued landscape of the western plains in this part of Alberta.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2001-348. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 20: Peace River, British Columbia. This photograph shows the typical landscape of the Peace River valley in British Columbia. Fort St. John is in the background to the right, and homesteads can be seen along the river.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-593. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 21: Valley of Battle Creek, Saskatchewan. This photograph, which looks toward the northwest, was taken in the valley of Battle Creek in the vicinity of the Cypress Hills Plateau, southwestern Saskatchewan. One of the three benches that lead up to the Cypress Hills Plateau can be seen on the left of the valley. The vegetation of brush and small trees is confined to a narrow strip along the creek. Visible in the distant background is the wooded crest of the Cypress Hills Plateau.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2001-338. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 22: Qu' Appelle Valley, Saskatchewan. This photograph, taken in the Crooked Lake area north of Broadview, Saskatchewan, shows the Qu' Appelle Valley of eastern Saskatchewan. This valley was carved into glacial sediments by meltwaters flowing from Alberta and Saskatchewan into glacial Lake Agassiz in southeastern Manitoba about 10 000 to 12 000 years ago. At this point, the width of the valley averages 2.5 kilometres, and its depth is about 120 metres.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2001-342. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 23: Red River, Manitoba. This photograph depicts a series of meanders along the Red River near Letellier in southern Manitoba. In the foreground is a ‘goose-neck’ meander, named after the very narrow ‘land bridge’ between the entrance and exit channels of the meander. The river will eventually erode through the ‘goose-neck’ and take the shorter, more direct route down the valley. This will cause the meander to be cut off. Eventually, the ends of the ‘cutoff’ meander will fill with sediment, sealing the channel and forming an oxbow lake along the valley bottom. Note the rectangular fields, reflecting the massive agricultural development of this region. The landscape of the Red River valley is very flat and almost featureless, and the soils are composed mostly of clay. These characteristics contribute to the frequent occurrence of spring flooding.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-686. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

The Cordillera

The Cordillera is divided into three large linear zones called the Eastern System, the Interior System and the Western System. Each system is further divided into areas and subdivided into mountains, ranges, plateaus, hills, valleys, trenches, basins and plains. Each has its own geological and physiographic characteristics. The Cordillera is also divided transversely into a number of segments by east-west belts of relatively low terrain.

In the Interior and Western systems, some landforms have been produced by volcanic processes. Most striking, however, are three great shield-like volcanoes in the northwestern part of the Interior Plateau and a group of similar volcanoes on the Stikine Plateau. Also on the Stikine Plateau are a number of flat-topped volcanoes that erupted during the Pleistocene Epoch (the Ice Age between about 80 000 and 10 000 years before the present time). A large number of small volcanoes and cinder cones occur singly, in line or in groups. These range in age from pre-Pleistocene to within a few hundred years of the present and vary in height up to a few tens of metres. For more information, refer to the map on Major Volcanic Areas in Environment / Natural Hazards.

The following photographs are examples of landscape from the Cordillera.

Figure 24: Upper Kananaskis River, Alberta. This photograph shows the formerly glaciated valley of the upper Kananaskis River. The U-shape is caused by glacial erosion along the bottom and sides of the former, stream-carved valley. The glacier-covered continental divide lies along the right (west side) of the view; below it is a tarn, or alpine lake, whose basin was carved by glacial ice. The knife-edged peaks and ridges along the higher elevations are known as arêtes and dominating the skyline is the pyramidal peak of Mt. Joffre. This latter feature is described as a horn and owes its origin to erosive action on all sides of the peak. The general elevation of these mountains is about 3000 metres. In all, this landscape is an example of glaciated, mountainous terrain.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2001-302. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 25: Pelly Mountains, Yukon. This photograph, taken near the Pelly Mountains in the southeastern Yukon, shows a valley whose very pronounced U-shape indicates that it has been modified by a glacier. A glacier’s base has many embedded rock fragments that erode the surfaces beneath them, changing the landscape significantly.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-611. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Great Lakes - St. Lawrence Lowlands

The Great Lakes - St. Lawrence Lowlands border the Shield on the southeast, extending from the west end of Lake Huron and the head of Lake Erie northeasterly to the Strait of Belle Isle. They comprise three subregions: the West Lowland, the Central Lowland and the East Lowland. The lowlands are plain-like areas that were all affected by the Pleistocene glaciations and are therefore covered by surficial deposits and other features associated with the ice sheets.

- The West Lowland is broken into two parts by the Niagara Escarpment, which extends from the Niagara River on a sinuous westerly and northwesterly course to the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island. The surface west of the escarpment slopes gradually southwestward through an area of rolling topography of low relief. East of the escarpment, the land rises gently northward from Lake Ontario;

- The Central Lowland includes the area between the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers, straddling the St. Lawrence as far as the city of Québec and extending a short distance beyond the city on the north shore only. The land is rarely more than 150 metres above sea level, except for the Monteregian Hills, which consist of intrusive igneous rocks

- Finally, the East Lowland includes Anticosti Island, Îles de Mingan, and several small areas bordering the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Strait of Belle Isle, as well as the Newfoundland Coastal Lowland.

The following photographs show examples of landscape from the Great Lakes - St. Lawrence Lowlands.

Figure 26: Trois-Rivières, Quebec. This photograph shows the St. Lawrence River valley in the area of the city of Trois-Rivières in Quebec.

Source: D. Lacasse, Natural Resources Canada

Figure 27: Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade, Quebec. This photograph of the village of Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade and the Sainte-Anne River in Quebec shows the agricultural lands in the St. Lawrence River valley.

Source: D. Lacasse, Natural Resources Canada

Appalachian Uplands

The Appalachian Uplands extends from southern Quebec and Gaspésie to encompass New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and the island of Newfoundland.

On the island of Newfoundland, the Appalachian Uplands comprises three highlands that form a group called the Newfoundland Highlands. They are rugged with steep slopes and elevations vary from 180 to 820 metres. On the east side, the Atlantic Uplands of Newfoundland lie between 180 and 300 metres in elevation, and the Newfoundland Central Lowland extends from sea level up to 150 metres. Its surface is gently rolling and generally underlain by glacial sediments.

Nova Scotia is divided into three highland areas, three uplands and several small lowlands. The Nova Scotia Highlands include the Cobequid Mountains in the west, the Antigonish Highlands in the centre and the Cape Breton Highlands to the northeast. South of these highlands lay the Nova Scotia Uplands and the Annapolis Lowlands.

New Brunswick comprises three large units: the New Brunswick Highlands; the Chaleur Uplands, which cross the Quebec–New Brunswick border; and the Maritime Plain, which stretches around the coast of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia from the south shore of Chaleur Bay and includes Prince Edward Island and Îles-de-la-Madeleine.

In Quebec, the Chaleur Uplands are bounded on the north by the Notre-Dame Mountains, which extend from near Thetford Mines to Baie de Gaspé. In the Notre-Dame Mountains area, there are the Chic-Chocs Mountains which have the highest elevation at more than 1230 metres in the north. To the southwest, the summits are lower, like the areas of Mégantic Hills and Sutton Mountains, which merge with the Eastern Quebec Uplands. The Sutton Mountains are a continuation of the Green Mountains of Vermont; and the Mégantic Hills lie astride the Canada–United States boundary and are part of the larger White Mountains of the New England states.

The following photographs show examples of landscapes from the Appalachian Uplands.

Figure 28: Gros Morne National Park, Newfoundland and Labrador. This photograph, taken in Gros Morne National Park on Newfoundland, shows a wide U-shaped valley 23 that was formed by erosion from repeated advances of glaciers from the Newfoundland ice sheet.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 2002-089. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Figure 29: Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. This photograph, taken on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, shows the flat and virtually unmodified surface of the highlands, which contrasts with the branching network of river gorges that incise its margins.

Source: Geological Survey of Canada, photograph number 120182. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2005 and courtesy of Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada.

Definitions of underlined terms

- Arete

- Steep-sided mountain ridge also spelled arête

- Escarpment

- A long steep slope at the edge of a plateau

- Esker

- Sinuous ridges composed of glacial material deposited by meltwater currents in englacial tunnels. Their orientation is generally parallel to the direction of glacial flow, and they sometimes exceed 100 kilometres in length.

- Fjord

- Deep and narrow glacial valley invaded by sea water after the retreat of the glacier

- Ground ice

- Ice formed into the ground

- Horn

- A pyramidal peak with three or more distinct faces steepened by glacial undercutting

- Ice wedge

- Piece of ice, generally has the shape of a wedge with the apex pointing towards the bottom. This ice is vertically foliated and is generally white.

- Igneous rock

- Rocks that are formed from molten materials that come from the depths of the Earth. They are also referred to as magmatic rocks.

- Nunatak

- Inuit-derived word describing a mountain completely surrounded by an ice cap

- Patterned ground

- Ground where the surface presents regular patterns such as circles, polygons or parallel lines

- Permafrost

- A layer of permanently frozen soil and rock. The active layer of permafrost refers to that portion of the ground that freezes in winter and thaws in summer; this layer is usually less than one metre in depth.

- Pingo

- Small hills with an ice core growing by water injection; they are covered with soil and vegetation

- Pleistocene

- An epoch of the Quaternary period, after the Pliocene of the Tertiary and before the Holocene. Pleistocene was between about 80 000 and 10 000 years before the present time.

- Precambrian rock

- Rock that originates from the geologic period in history from about 4.5 to 5 billion years ago to about 570 million years ago. Precambrian rock covers about 75% of the land area of the earth.

- Sedimentary rock

- Sedimentary rocks are the product of the consolidation of loose sediment that has accumulated in beds. These sediments settle gradually under the weight of overlying beds and are transformed into solid sedimentary rock by cementation.

- Surficial deposits

- Unconsolidated materials covering the ground

- Thermokarst

- Karst-like topographic feature produced in a permafrost region by the local melting of ground ice and the subsequent settling of the ground.

- Till

- Any sediment that is transported and deposited by a glacier without being sorted by meltwater. It consists of clay, sand and large rock fragments that are deposited in irregular sheets or in ridges called moraines.

- Tundra

- The treeless area to the north of the boreal forest. Tundra vegetation includes low, matted and erect shrubs and herbs such as cottongrass.

Physiographic Regions

Map Source

Map. Physiographic Regions of Canada. 1254A. Scale 1:5M compiled by H.S. Bostock. 1967. Geological Survey of Canada.

Map References

Bone, R. M. 2003. The regional geography of Canada. Don Mills, Ont: Oxford University Press.

Douglas, R.J.W. (Scientific Editor). 1972. Geology and Economic Minerals of Canada. Geological Survey of Canada.